#5: A Culture of Cowardice (part one)

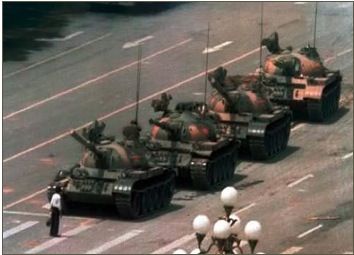

Who are the exemplars of courage in our culture? To whom does America look when seeking heroes to be our role models? Lady Gaga? Bill Moyers? Dennis Kucinich? Robert Downey Jr.?

It seems to me that the courageous have become an endangered species…and not just in society– but in the Church.

Think about it.

Wikipedia defines an endangered species as a population “at risk of becoming extinct because it is either few in numbers, or threatened by changing environmental or predation parameters.” Can you see that all three conditions are true of the Church today?

We’re left with what I call a Culture of Cowardice.

Back in the early 1990’s Dr. Edwin Friedman described America as “a seatbelt society”  that is oriented more toward safety than adventure. In A Failure of Nerve he notes that America has become so chronically anxious that our society has gone into an emotional regression toxic to courageous, well-defined leadership. One effect of societal anxiety is a reduced pain threshold. The result: comfort is valued over the rewards of facing challenges. A culture like this has no stamina in the face of difficulty and crisis.

that is oriented more toward safety than adventure. In A Failure of Nerve he notes that America has become so chronically anxious that our society has gone into an emotional regression toxic to courageous, well-defined leadership. One effect of societal anxiety is a reduced pain threshold. The result: comfort is valued over the rewards of facing challenges. A culture like this has no stamina in the face of difficulty and crisis.

How well does this describe the contemporary Church?

In our commitment to “being nice” we prioritize togetherness over actually making a difference. In our desire to feel good we bury our heads in the proverbial sand while the culture around us sprints toward its own destruction. According to Friedman dissent is discouraged, feelings take precedence over ideas, peace over progress, comfort over anything new, and cloistered virtues over adventure. The press within church for togetherness smothers bold, daring, world-changing action – like we see in the Book of Acts – and those who are courageous enough to engage it.

What emerges, stunningly, is a culture that is so “nice”, so fixated on empathy that it organizes itself around the most immature, most dependent, most dysfunctional members.

Or, haven’t you noticed?

The average church in America has fewer than 80 in attendance and has been in decline for decades, fewer than 5% of their members tithe and the majority contribute nothing at all, and most fail to see a single convert to the Christian faith a year.

Who has hijacked the agenda in most of America’s churches? The least courageous, least responsible, and least emotionally and spiritually mature have taken most churches captive.

Courageous leadership, by nature, is decisive. And, the Latin root of decisive means “to cut”. But, it is not “nice” to cut anything away, to cut anything off, to cut anything out—even a toxic presence that – like a parasite – survives by sucking the life out of those who are healthy. To lead with heart is to stand for what’s best, simply because it is best—even when it is unpopular. Even when it provokes opposition from misguided stakeholders within the Church.

Courageous leadership, by nature, is clear. Such a leader is unapologetically clear about who she is, the difference she is committed to make in the world, her values and priorities. The clearer you are as a leader, the clearer people around you will be. And, therein lies the problem. As pastors, we don’t always like what that clarity reveals. As you become more and more clear as a leader, more and more people will decide they’re not “up” for going where you’re going. Stay foggy and many will stick with you, wandering in impotent ambiguity.

Courageous leadership, by nature, is disruptive. Courageous leaders routinely disrupt dysfunction. They regularly challenge their own preference for comfort—and that of those they lead. Many interpret their leadership as crisis-inducing. Friedman notes that crises are normative in leaders’ lives. These crises come from two sources: those that just arise, imposed on the leader from forces outside that leader’s control and crises that are initiated simply by the leader doing exactly what he or she should be doing. Yet, how reluctant is anyone in church leadership to lead in such a way as to invite a crisis for long-standing church members?

As a leadership coach and consultant to pastors, my life’s work is to champion Christian influencers to find their hearts and to fully re-engage them in this great, important struggle to stir the Church from its slumber. There is no altogether “nice” way to do this.

Just five verses into his story, Jonah is sound asleep below decks, aboard a ship imperiled in a brutal storm. The terrified captain races below, is stunned to find Jonah asleep — in so important a moment – wakes him demanding: “How can you sleep? Get up and call on your God! Maybe he will take notice of us, and we will not perish.” [Jon1:6] Get this: it was not a follower of Yahweh who stirred Jonah from slumber—calling him to take action with God lest the “community” they were part of be plunged to ruin.

Look around you. Is not the community around your church caught in a destructive storm? A moral, ethical, spiritual, relational hurricane that wills to destroy the fabric of American society? Don’t you see the storm buffeting the Christian faith—driving it to the nether regions of the culture?

To awaken the Church, her leaders must first rouse themselves. Then, embracing the opportunity provided by this life, they can stand clearly, decisively, and disruptively to awaken their churches to enter the glorious and dangerous fight for the redemption of the un-churched near them.

What else would a courageous Christian do?

Kirk,

Wow…way to cut to the heart! Once again your words have brought clarity to issues I’m facing. I like to be “nice”, not confrontational. Perhaps it’s time for me to say, “No more Mr. Nice Guy.” Ok…perhaps that is a bit extreme, but I do recognize the need to step up and move forward. Thanks again, buddy.

Don

Kirk,

This is good stuff. The book Failure of Nerve has been challenging to me. I am working on being a courageous leader.

Jim

Friedman’s insights are quite remarkable, relevant and profound.

They need to be discussed in light of our Christian values for “harmony” “compassion” and regard for the “less comely parts” of the Body (“least of these”) so that truth and error in these issues can become more distinct. I hope you will clarify these issues further in future communications.

Bill, thank you for your thoughtful and appropriate perspective. Clearly, we are called to respond with compassion – literally to “suffer with” – for those who suffer loss, and to posture our hearts in humility and not arrogance or elitism toward those within and outside the Church. As we do, we also are called to drive out darkness, to be more than conquerors, and to stand in society in such a way as to model a clear and compelling alternative to the shallow self-centeredness of the common life. The dance, it seems, is to suffer with those who are suffering without supporting irresponsibility, entitlement, a victim-paradigm, and childishness in our faith community.

Consider, for example that fewer than 5% of regular church goers tithe.

Fewer than 40% give any money at all, in a given year.

I wonder how the orientation of the Church to make it easy for people to participate — without any real, clear expectations from them (for example to tithe, to serve, to grow beyond the perimeters of their comfort-zone) to stand responsible to the community of faith where they are fed and cared for — has contributed to the stunning shallowness characteristic of American Christianity today.

I wonder if our concern for the happiness of our people, our rush to quickly comfort the “distressed”, our willingness to water-down the messages we bring (so as to, for example, not offend the proponents of same-gender relationships), our limitless generosity with counseling sessions, home and hospital visits (whether the recipients of this generosity ever contribute to the community with their time or money), even our practice of giving to the poor without regard for what may have l brought on their poverty, might represent a philosophy of ministry that is more popular than biblical. [I tim 5:8, 2 Thess 3:10, Mk 10:45, Gal 5:19-21, Mt 7:10-13, Eph 4:28, Lk 6:38, 2 Cor 9:6, Eph 4:15-16]

The lament of most pastors I know is that the “80-20 Rule” is alive and well in their churches. 20% of the people do 80% of the work. If “every system is perfectly designed to produce the results it is getting” then, we would be smart to ask how our philosophy of ministry has perpetuated the 80/20 condition. Why shouldn’t we see that go, for example from 80/20 this year to 70/30 next year, 60/40 the year after, then 50/50 the year after that? What if the evidence of a maturing congregation is the growing responsibility of church attenders, at least in financial giving and serving others?

How do we, as leaders, blend compassion with challenge?

How do we refuse to coddle and soothe the immaturity of our people and still lend comfort where appropriate? Maybe the answer lies in our vision for our people– is it that they be free from distress or that they stand as mature, influential, image-bearers of Christ– the same Christ who threw over the money-changers tables, refused to settle the score for the squabbling siblings, rebuked Peter publicly, offended his audience in John 6, exposed the hypocrisy of the religious elite, and healed all ten lepers.

Thanks for your insight, Bill. I have great, great respect for you, my dear brother!